About this episode

Neil Eggleston

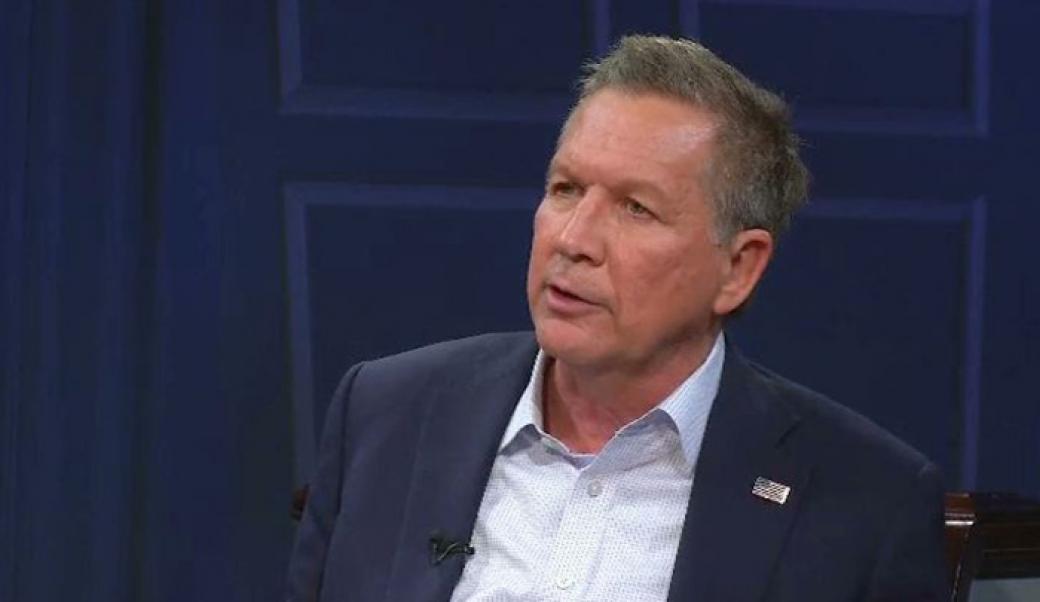

When controversy erupts around the highest levels of the US government, behind the scenes are the government lawyers defending the presidency itself. The Office of the White House Counsel is charged with giving the president legal advice and also ensuring that the White House is broadly following the law. These lawyers must balance the interests of the current president while also protecting the power and privileges of those who will hold the office in the future. But whose interest does the White House counsel ultimately represent? Is it the president, his office, or the American people? Our guest in this episode is NEIL EGGLESTON, who served as White House counsel from 2014 to the end of President Obama’s term. He’s now a partner at the DC law firm Kirkland & Ellis.

Transcript

0:42 Douglas Blackmon: Welcome back to American Forum. I’m Doug Blackmon. When controversy and legal conflicts erupt around the highest levels of U.S. government, the first line of defense in the eye of the public and media are spokesmen and spin doctors. But behind the scenes are the government lawyers who represent federal agencies, top officials, and at the White House, the office of the presidency itself. In the short, scandal-plagued time that President Donald Trump has been in office, those legal teams have already gotten a vigorous workout—along with a growing army of private criminal defense lawyers now representing the president and others personally, as well as many high-ranking members of his administration. In the midst of all that, the Office of the White House Counsel is charged both with giving the president legal advice, but also ensuring that the White House is broadly following the law on many levels—what it’s legal limitations may be, what power the president has in appointments and executive orders, and how to handle the balance the interests of the person currently serving as president while also protecting the power and privileges of those who will hold the office in the future. And unlike the private lawyers who may defend a president personally, the White House Counsel faces a unique legal jeopardy—he or she can, in some circumstances, become a target of federal criminal investigations, as well, as in the case of Richard Nixon’s White House Counsel, John Dean, who went to prison for his role orchestrating the Watergate cover-up. But whose interest does the White House Counsel ultimately represent? Is it the president, his office, or the American people in some fashion? Our guest in this episode is Neil Eggleston, who served as White House Counsel from 2014 to the end of President Obama’s term. He’s now a partner at the Washington D.C. law firm Kirkland & Ellis. Thank you for being here.

W. Neil Eggleston: Thanks, Doug. Happy to be here.

02:28 Blackmon: So, let me paint an imaginary picture for you, okay? It is January 2015, or thereabouts. You’re the White House Counsel. Newly nominated—or let’s say she’s been confirmed. Deputy Attorney General Sally Yates comes to visit you and says that National Security Advisor Susan Rice [inaudible] this is all made up. No suggestion that any of this—true. She comes to you—Sally Yates comes to you and says, “Susan Rice has had contacts with a foreign government that were picked up on by intelligence agencies and that there are concerns about. And, in fact, FBI agents went and talked to her about this, and we believe that she misled these FBI agents about what happened, and that, and subsequently, this—a false story has also been shared inside the White House and has been shared with the American people about this sequence of events.” So, the deputy attorney general relays this to you, as the White House Counsel. Would your response have been, “Why does the Justice Department care about this?”

Eggleston: So, Doug, not a bit. If I got that advice from Deputy Attorney General Yates, at the time, I would have gone into hyperdrive. And my goal would have been to protect the President of the United States and the presidency. If there’s a suggestion that somebody at senior levels of the White House is engaged in misconduct, false statements, possibly illegal conduct, that’s exactly the kind of information that I want brought to the White House Counsel. And that’s important that we act on immediately. I would have gone to the Chief of Staff, probably first, and told him, Dennis McDonough about it, and we would have immediately gone to talk to the President of the United States. And, you know, how much looking we would have done before making some sort of determination, I think the facts would have to develop a little bit further, but we would have acted on that, absolutely, immediately. There was a suggestion that possibly the National Security Advisor, in your hypothetical—National Security Advisor had been involved in improper, possibly illegal conduct. And those kind of people, if he had actually engaged—or she, in your hypo—engaged in illegal conduct, person can’t be working in the White House and can’t be representing the American people. We would have worked on—we would have moved on that immediately, and I never would have said—I, just having read about what did happen—Ms. Yates was, I think, bringing information so that the White House could act on it. It wasn’t—she wasn’t articulating a Department of Justice interest. She was bringing it to the White House because she expected the White House to act on it. If she brought it to me, we would have acted on it, absolutely, immediately.

05:16 Blackmon: And, of course, the hypothetical that I laid out for you, the parallel we’re building off of is that, at the very beginning of the Trump administration, that the story we all know well, but to reprise it anyway—but that it developed that the National Security Advisor, General Michael Flynn, had had conversations with the Russian ambassador and then, apparently, had described those conversations inaccurately, or at least not in a completely forthcoming way to the vice president, who then repeated those descriptions to—publicly, to the American people. And then FBI agents did visit General Flynn, and apparently, he was not forthcoming or maybe was—answered their questions in a way that was untruthful, which is—if that was the case, would itself be a felony, [Eggleston: Right.] arguably. And so, uh—and then, the—then acting Attorney General Yates visited the White House Counsel, Don McGahn, and laid this all out, and Mr. McGahn’s response was, one of his responses was, in the course of that, “Why does the Justice Department care whether one member of the administration misled another member of the administration?” There has been some suggestion that a sequence of events like that was just sort of the sloppiness of an administration that was only a few weeks old, and maybe forgivable, in some sense, that it took several weeks further before there really was action taken about all that. But does that hold, whether specific to that or another situation? My sense is that—job of the White House Counsel’s actually to be one of the main people who really does know what he or she is doing, all the time.

FACTOID: Flynn was fired 18 days after Yates warned he could be compromised

Eggleston: Yeah, so I think, you know, the president takes over the nuclear codes on the first day, and the White House Counsel has to take over the duty of protecting the White House on the first day. And there’s not a, in my view, a, you know, getting ready period. That’s what the transition period is about. And they really should have been in a position—look, I don’t know—I’ve read the same reporting as you have. I don’t actually know whether it’s all accurate or not. But they had to be ready to go from, really from day one. There’s always a tension, and I suspect this what—is what happened, which is if you act, you’ve created a story and if you don’t act, maybe it’ll go away. But, you know, most of us learn in our childhood that the second one doesn’t actually ever work. And (laughter) so this was a situation, I think required immediate action, and they had to be ready to go on day one and confront those kinds of problems, ‘cause all sorts of those kinds of problems could have happened on day one of the presidency.

07:52 Blackmon: Let me ask you about one specific thing that has come up in some of the reporting in recent weeks, and that is that apparently there was a FISA warrant issued. Let’s just assume that this is the—that what The New York Times [has seen?] and others have reported is, in fact, the case, unless you know otherwise. But apparently, there was a FISA warrant issued that allowed the government to wiretap Paul Manafort, who was a—the campaign manager for the Trump campaign from May to August of 2016. But there was a warrant in 2014, and then another one issued in 2016. And both of those happened—covered periods of time that you were [Eggleston: Right.] in the White House. But White House Counsel, I’m assuming, [even though I’ve?] just wasted a whole lot of time explaining this, the White House Counsel has nothing to do with that, right? So, you would’ve—you—

Eggleston: Absolutely nothing to do with it. I didn’t know it, they wouldn’t report it to me. It was—assuming the reporting is true, it was an investigation of a particular individual in connection with a larger investigation into Russia influence or whatever. Probably less true in 2014, actually, is probably more of a 2016 issue on Russian influence. But a specific investigation of an individual, I didn’t not, I was never told about that. If somebody had tried to tell me about it, I would have told them I didn’t want to hear about it, and I—there—I would not have heard about that

09:13 Blackmon: It’s easy to think, based on movies and sort of melodramatic assumptions about how politics work and how government works that, well, of course, an investigation conducted by the FBI into a campaign official of a candidate in the opposing party—well, of course that’s something that the sitting White House at the time knows about. And has had some—it’s a little bit like how in the newspaper business, no one will ever believe a reporter when they say, “I really don’t even know the people who write the editorials,” you know? And then, “They really don’t tell me who to [Eggleston: Right.] who to write bad stories about. You know, it just doesn’t happen.” Nobody ever believes that. And in a similar way, it’s very difficult for people to really accept the idea that you could have the Department of Justice investigating Donald Trump’s campaign manager and obtaining this very special kind of search warrant, and the White House know absolutely nothing about it. But that is how it works, right?

Eggleston: It’s how it works, and if you think about it, it’s a very good example, which is if people thought—if the American people thought that the FBI was a political tool that could be turned loose on political opponents, that would be, I think, quite damaging to the FBI, and would be quite damaging sort of to our democracy and the way it works. The power to investigate is a gigantic power in this country, and it’s important. I mean, it’s such a good example, because the notion that anybody in the White House would suggest—maybe say the Obama White House—suggest, “Maybe you should be doing an investigation of Paul Manafort,” that would be directing a use of a—of this resource to advance a political goal, and I think that that would be wrong on so many different levels. And it’s really important that that really not happen.

FACTOID: Trump fired FBI director Comey amid FBI Russia investigation

And I will say, there’s been a lot of complaint about leaks out of—sort of the FBI and various other places, but in a circumstance where the FBI might feel that it’s being used for other than its traditional purposes. I have to say I think leaks are all but inevitable, and so I think the kinds of leaks we’ve seen out of the FBI, kind of leaks we’ve seen out of the intelligence community, are pretty much to be expected, given the environment that we’re in. And so, I’m not a bit surprised. We, you know, we definitely had leaks in the White House and in our administration, but not really—if you think about it, at least from my point of view, pretty benign ones, and nothing particularly significant, I think, that occupied attention for any significant period of time. We never did witch hunts and to figure out who the leaker was going to be, ‘cause we had things to do and we weren’t going to spend our time—you know, that’s pretty disruptive, doing that kind of stuff. Some of that is just to be expected. I think there have been more in this administration, but I think it’s because of—sort of the attitude of the administration toward some of these institutions that are resistant to what they’re being—sort of the way they’re being treated.

12:29 Blackmon: And all of which you’ve been talking about, I think, speaks to this issue of—that again, comes back to the importance for all parties of preserving the future powers and future capacities, particularly of the presidency, because I think what comes from all of that is that we’re now in a situation that—say, for instance, next week, it—revelation came up that a grand jury’s been impaneled in the southern district of New York and there actually is a criminal investigation under way into the Clinton Foundation. You know, something having to do with donations to the Clinton Foundation, that the FBI’s conducting this and is bringing evidence to a grand jury. Well we, particularly today, I think we—the very first question that other journalists would be asking and that lots of citizens would be asking is: is this just a political witch hunt coming from the White House? And I think that the—and the strongest evidence that it might be, would be—the most persuasive evidence that maybe that’s possible are the claims that the investigations of the Obama years were coming from the White House. And so, this—the danger of politicizing what desperately needs to be as clinical as possible in action of government in terms of criminal prosecutions—

Eggleston: So, absolutely my view—if there were a prosecution such as that, immediately a significant percentage of the population would think it was initiated by the Trump White House and as political retaliation, I don’t know for what anymore. He won, so—but as some sort of political retaliation. And I—I was also an Assistant United States Attorney in the southern district of New York and loved that organization. And the notion that those kinds of decisions would be politicized and that people would think that they were done on the basis of Republican, Democratic kind of issues—I just think that it’s quite damaging. And remember, there are a lot of public corruption cases brought all over the country and by [main?] Justice, and that’s—they’re either against Republicans or Democrats. And the—there’s a public integrity section of the Department of Justice that is insulated pretty much from the rest of the organization. Same in the U.S. Attorney’s office. But I cannot—I just can’t tell you how strongly I feel—how much we’ve lost if people think that those prosecution decisions are made on the basis of politics and not on the basis of whether or not an investigation or indictment or—whether is justified. I think that we have lost an enormous amount, and I—and so, I hope this stops, frankly.

15:00 Blackmon: And your history, the course of your career as an attorney working in government service includes not just your time as White House Counsel, but as you were describing, also in the Clinton White House related to the Whitewater scandal and other issues. But then, before that, as a—working for congressional—connection to congressional investigation into Iran/Contra and so—go over fairly long period of time. I do sometimes find it extraordinary, really, that we seem to have forgotten that, while there was a lot of unsatisfaction—dissatisfaction with the final outcome, for instance, of the Watergate—the resolution of the whole Watergate process and the fact that President Nixon was, in fact, pardoned in a sort of curious kind of way by his successor—there was a lot of controversy about that at the time.

FACTOID: Ford pardoned “all offenses” Nixon “may have committed” as president

But in the final analysis, the notion that the thing that other societies around the world, again and again, are most impressed about with American democracy is our ability to transition from one leader to the next, no matter what the political environment may be, without going back into civil war and without doing the kinds of [Eggleston: Right.] damaging behaviors that make it impossible to govern in the future. And so, the idea of putting an ex-president in prison, even if they did something really bad, I think we—many of us would say that’s probably the wrong thing [Eggleston: Right.] to do. We don’t want that outcome because of the corrosive consequences of it. But it seems that we’ve lost that idea, and that under some circumstances you could end up with—if a case could be made against Hillary Clinton that there would be a lot of people who’d say, “Yeah, put—lock her up,” as was said.

16:41 Eggleston: So, I—I agree with that. And, you know, one of the most consequential things that have happened in American history is President Washington determining to quit after two terms, so that immediately, on his successors, there had to be a determination of how you have the next generation, the next generation, the next president, the next president.

FACTOID: 22nd Amendment ratified in 1951, limits president to two terms

And by making a decision to quit after two terms, he put that process, I think, really in place, and we’ve lived by that. And frequently, Republicans follow Democrats and Democrats follow Republicans. It’s kind of the way it happens in our system. And we’ve always done it, and as you say, Doug, this is—unlike lots of countries, this is one of the things that we are really known for. We are a real democracy where these kinds of—use of power to get at your opponents in an inappropriate way just doesn’t happen the same way it does some other places

17:37 Blackmon: Well, the—another tradition, another norm has been that, with the transition of power, that the president—the former president typically recedes from public life, at least for a pretty long period of time, and—but to some degree never really completely reappears on the public stage. And, to some degree, very significant advisors to the president, officials, tend to do some version of the same. That was your approach to—after the end of the Obama administration. Didn’t have much to say about what was happening in the White House. But now, recently, you’ve begun to say more about it and have been fairly pointed in some of your criticisms. But why is that? Why were you quiet about it and now why are you talking about it?

Eggleston: I made a decision that I wanted to be as available as my successor wanted me to be. If he wanted to call me for advice, I was fortunate enough that I was the last three years of administration. I knew my predecessor, had known her for years. I knew her predecessor and I knew the first one all pretty well, and they were all quite accessible to me if I wanted to call and ask for advice. There was really no immediate predecessor that Mr. McGahn could call, and I wanted to make sure that I was available to him, and I thought if I were speaking out and if he was worried that I might relay—if he called me with a question—I said to him at one point, “Look, it doesn’t matter how stupid the question is, because you don’t know anything yet. You just got here. You never served here.” So, I really wanted to make myself available, and I thought if I spoke, it would not—I would diminish the likelihood he would call me. And as I say, I care so much about that institution that I really wanted it to be successful, and I wanted to make myself available. He made a determination not to avail himself of that, which is completely, you know, within his prerogative. But I’m just, as you can probably tell from what I’ve said today—I’m so concerned about the impact of various things happening to our institutions—this is not a political, Republican/Democratic issue, and I hope people aren’t thinking that I’m speaking from that today, ‘cause I’m not, really. But I’m sufficiently worried about what’s happening to our institutions that I thought it was time for me to speak a little bit more about that issue and how important it is that we continue to respect and hold up for respect our institutions. And that’s really the theme of what I’m starting to talk about today. I’ve generally not been talking, for example, about the Russian investigation. That’s a completely separate issue. But I’m concerned about our institutions and the way they’re being treated.

20:00 Blackmon: But you’ve talked about that the Syrian airstrike ordered by the president was actually—and something which, of all the various decisions made by the president related to international affairs of any kind, that’s probably the one that’s gotten the most support from people who were not natural supporters of the president, that that was a good thing to do.

FACTOID: Airstrike was response to Syrian gas attack on its own citizens

But you’ve said that the reasoning for the airstrikes, the legal basis for—particularly international law, explanation for why it was legal to do has never really been offered adequately. You’ve talked about the first version of the travel ban that became so controversial that—the failure of the White House to establish a clear record of facts demonstrating an actual necessity of—for something like that to be done, that it was instituted too soon after the Inauguration for, you know, for the—for a basis for it to have been established. Same with the transgender military ban, which—still unclear whether that’s actually happening or not, but no real set of facts offered up. Similar kinds of observations you’ve made about the Dreamer Act, you know, the—but essentially, again and again, is there an actual factual basis for these very dramatic decisions being made that have such big implications? And you’re saying that there needs to be such a basis and there hasn’t been one. But why is that? If we elect somebody to go to Washington to drain the swamp and blow up institutions, then why do we need to go through all of this—the persnickety details that you want?

Eggleston: Well, let me use the transgender ban in the military just as a—as an example, although you’ve given a number of examples.

FACTOID: Trump tweeted ban on transgender military service “in any capacity” And this comment is apart from whether people think that transgender people should be in the military or not in the military. But under the Obama administration, the Department of Justice made a determination that transgender—that basically, anybody who wanted to serve in the military should be allowed to serve and we shouldn’t exclude people—we had long since not excluded people on the basis of their gender, and this was just another—or on—or whether they’re gay or lesbian, and that this was another example. If someone wants to serve in our military and protect our country, they should be allowed to do it. And there was a determination made that it was neither—it had no impact on readiness and did not have an excessive cost. So, when President Trump determined to do that by tweet, and apparently, if you believe the reporting is true, surprising his Defense Department, it leads you to conclude that the Defense Department had not been consulted on readiness or cost before he made that determination, in which case, it’s hard to figure what basis he used to make that determination other than animus against transgenders. [But?]—I can see him ordering the Department of Defense, for example, to take a new look at that, and “I have new leadership over there, I want you to tell me: what do you think about the impact on readiness and what do you think about cost?” And then making a determination, because then he’s made a determination that appears to be related to the defense of the country. And that—the Department of Defense ought to be related to the defense of the country, as opposed to an animus against transgender.

FACTOID: Rand Corp. study: 2,500 to 7,000 trans active-duty military members And so, by not creating any sort of a record, I think he leads to a conclusion that this is not based on a readiness and a defense of the country rationale. So, that’s just a—example. I pick it—it’s probably a slightly controversial one, ‘cause there are probably people even in this room who would not necessarily think that transgenders should serve in the military, but what then happens is a sort of a series of lawsuits that then challenge the president. He’s losing a number of them. He may ultimately win the travel ban case in the Supreme Court—

Blackmon: Yeah, particularly the travel ban, right, right.

Eggleston: But, you know, not the first one. They—[Blackmon: Yeah.] the first one, the Department of Justice abandoned, and they redid the travel ban. The second one, I don’t know how it’s going to come out, but it’s got a better chance than the first one, which—my view, because of the bad process, really had no chance of being sustained in the courts. And the Department of Justice itself recognized it had no chance when it decided to go back and redraft it. I think that’s not to our benefit. I lost some cases that I thought I should’ve won. I didn’t do DACA, that was before me. But DAPA, the successor, was on my watch.

FACTOID: DAPA protected undocumented parents of legal citizens, residents

So, I regarded part of my role, maybe a significant part of my role—was to avoid unforced errors, so that the policy people could do what they wanted to do. And I think that the White House Counsels in the Obama administration generally were pretty good at that. I think I was pretty good at that. Doesn’t mean we won all the time, but if we lost, we knew that there was a chance we were going to lose and we’d done our best to try to do it in a way that would be sustained. But the avoidance of unforced errors was a huge part of what I focused my attention on, and I think we were largely successful.

25:02 Blackmon: Well, thank you very much, and thank you for your, politics aside, your testimonial to the importance of these institutions that are the things that keep our politics civilized. And wherever we think our politics ought to go, I think you’re exactly right that that—that this could—if there’s—if we have a Waterloo, it may be this very thing. So, thank you.

Eggleston: Great, thank you, Doug.

Blackmon: If you’d like to share a comment or ask a question about this or any other episode of American Forum, you can reach me by email, with the one on the screen, or on Twitter @douglasblackmon. To watch other episodes of American Forum, visit us at millercenter.org. See you next week.