Watergate: The aftermath

August 8, 1974: Richard Milhous Nixon announces his resignation—and changes the presidency forever (Chapter 4)

Therefore, I shall resign the presidency effective at noon tomorrow. Vice President Ford will be sworn in as president at that hour in this office.

With those words, Richard Nixon became the first—and so far only—president to announce his resignation. He was doing so, he said, because “the interests of the Nation must always come before any personal considerations.”

“From the discussions I have had with congressional and other leaders, I have concluded that because of the Watergate matter, I might not have the support of the Congress that I would consider necessary to back the very difficult decisions and carry out the duties of this office in the way the interests of the nation will require. I have never been a quitter. To leave office before my term is completed is abhorrent to every instinct in my body. But as president, I must put the interests of America first.”

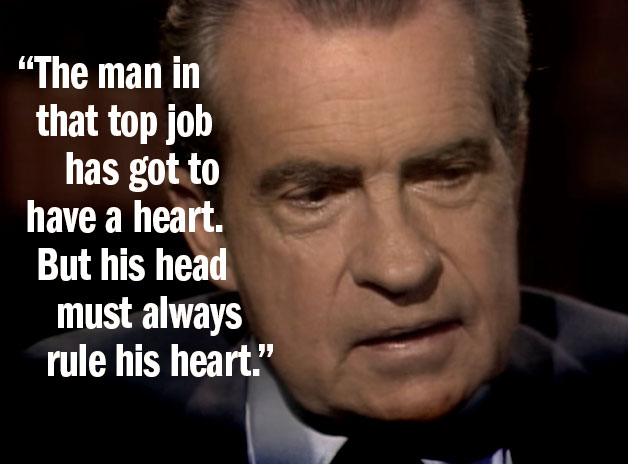

Nixon's downfall, however, came not so much from lack of congressional support—though that was the proximate cause—as it did from what is undoubtedly history's most transparent look into of the presidency of the United States. Nixon's secret White House tapes, uncovered in the course of the Senate Watergate hearings, revealed the truth about the Nixon presidency—and about Nixon himself. As much as Americans may have wanted to believe the president when he told them that he wasn't involved in the Watergate cover-up, the tapes proved otherwise. Americans could not reconcile Nixon’s public statements with the private recordings, and many could reach only one conclusion: Their president had lied to them.

I let down my friends. I let down the country. I let down our system of government—the dreams of all those young people that ought to get into government but they think it's all too corrupt. . . . I let the American people down. And I have to carry that burden with me for the rest of my life.

The pardon

For Nixon, one immediate problem was solved by his successor, President Gerald R. Ford. A month after the former announced his resignation, the latter told the nation he would pardon Nixon “for all offenses against the United States which he, Richard Nixon, has committed or may have committed or taken part in during the period from July 20, 1969, through August 9, 1974.” (Ford misspoke. The actual pardon was for Nixon's entire presidency, January 20, 1969 to August 9, 1974.) He did so, Ford said, to spare the country more and prolonged discord from Watergate, because Nixon wouldn't be able to get a fair trial and because “Richard Nixon and his loved ones have suffered enough.”

Many reacted critically. “President Ford has affronted the Constitution and the American system justice. It is a profoundly unwise, divisive, and unjust act,” said the New York Times. “It is an act of flagrant favoritism. It can only outrage and dishearten millions of his fellow citizens who thought that at last the laws of this nation would be enforced without fear or favor.”

Nixon had selected Ford as his vice president in the middle of the Watergate scandal after Spiro Agnew resigned in December 1973. Some suspected Nixon had extracted a promise of a pardon in exchange for the post, a charge the president vehemently denied. Ford had to appear before a subcommittee of the House Judiciary Committee to defend his action—only the second time a sitting president has testified before a congressional committee of inquiry. And just more than two years later, he narrowly lost the presidency to Jimmy Carter, a defeat that Ford and many others attributed to the pardon.

Time, however, has convinced many former critics that Ford was right. In 2001, he received the John F. Kennedy Profile in Courage Award for the pardon. “I was one of those who spoke out against his action then,” Senator Edward Kennedy said. “But time has a way of clarifying past events, and now we see that President Ford was right. His courage and dedication to our country made it possible for us to begin the process of healing and put the tragedy of Watergate behind us. He eminently deserves this award, and we are proud of his achievement.”

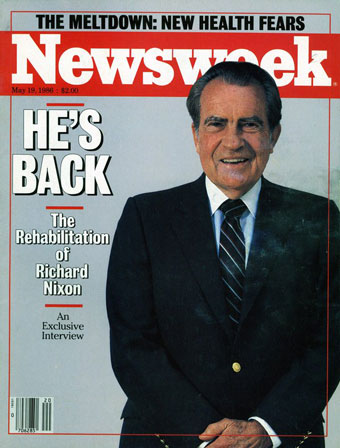

Nixon, the elder statesman

With legal jeopardy no longer an issue, the former president set out to rehabilitate himself and his reputation, to become a "new Nixon" one last time. His 1977 series of televised interviews with journalist David Frost and the 1978 publication of RN: The Memoirs of Richard Nixon gave him an opportunity to tell his side of the Watergate story—and injected badly needed cash into his bank account. By 1980 he was living in the New York City area and accepting the many opportunities to give his opinion on foreign affairs: For all the domestic turmoil his presidency had engendered, Nixon was still the man who had opened China, negotiated arms-control treaties with the Soviet Union, and brought to an end, no matter how painful, the Vietnam War.

Six more books followed. When Nixon finally passed away in 1994, his funeral was attended by every living president. "May the day of judging President Nixon on anything less than his entire life and career come to a close," said President Bill Clinton that day. But Watergate still resonates as the most memorable and significant aspect of Nixon's career.

The post-Watergate presidency

In the 1940s and '50s radio program “Mr. President,” America's chief executive was described as “the elected leader of our people, our fellow citizen and neighbor.” Immediately after Watergate, that characterization would have been hard to fathom. The nation was already distrustful and disoriented after the racial and cultural conflicts of the 1960s and the revelation that their government, under President Lyndon Johnson, had been hiding the truth about the Vietnam War. Nixon then put the country through a constitutional crisis and left the Oval Office in disgrace.

Seemingly overwhelmed by the office and its challenges, the presidents that followed—Gerald Ford and Jimmy Carter—found themselves unable to win reelection. The press focused its attention on unmasking whatever the president, and presidential candidates, might be hiding. Congress, too, became suspicious and wondered if it had ceded too much power to what was supposed to be a co-equal branch of government.

With the rise of Ronald Reagan, the luster of the presidency began to return. Good natured and self-effacing, Reagan won overwhelming reelection and overcame his own scandal: the Iran-Contra affair. Three of his four successors served a full eight years, even though one, Bill Clinton, had to survive what Nixon's resignation had precluded: impeachment by the House of Representatives and a trial in the Senate.

But the legacy of Watergate ultimately lies in the minds of American voters. Today, we don't seem to seek government experience or the right set of policies in our presidential candidates. Instead, what Americans seem to long for is authenticity, a person to trust and believe in.

During campaigns, presidential candidates assert that their opponent is ultimately untrustworthy—in essence, just another Nixon—a tactic Nixon himself embraced in his early campaigns. And yet, ironically, these kinds of black-and-white questions about character don't seem to lead to more trust in the president, public officials, or the government as a whole. Questions of policy can be debated in logical terms and are often ripe for compromise. Questions of trust often come down to feelings and emotions. It would be foolish to blame Richard Nixon for all of this. But more than four decades after the June 17, 1972, break-in at the Watergate office building, it would be equally foolish to forget its effects.