About this episode

January 20, 2017

Eliot Cohen, Jeremi Suri

The Trump presidency has officially begun. For some Americans, it’s exciting; others are wringing their hands. But either way, many of the issues President Trump will confront are very predictable. National security problems are almost inevitable. Job growth, immigration, and racial tension will test our new chief executive. So with this episode of American Forum, we are kicking off a series of programs to delve into the most critical issues that face almost every new president with national security experts Jeremi Suri and Eliot Cohen.

American Defense and Security

First Year 2017: National security in a Trump presidency

Transcript

0:51 Douglas Blackmon: Welcome back to American Forum. I’m Doug Blackmon. The Trump presidency has officially begun. For some Americans, it’s exciting; others are wringing their hands. But either way, this new administration is taking form—quickly, messily, unpredictably. But many of the issues that will most quickly confront President Trump are, in fact, very predictable. We know from history that national security or foreign policy problems are almost inevitable in the first year. It’s clear that job growth, immigration, racial tension, and a long list of other challenges will test our new chief executive in the months ahead. So with this episode of American Forum, we are kicking off a special series of programs, continuing through most of the spring, that will delve into the most critical issues that face almost every president during the first year in office, and will undoubtedly confront President Trump. This is the culmination of months of effort here at the Miller Center through our First Year Project, to identify the most urgent issues, assemble nonpartisan groups of experts to study them, and to make practical, nonpolitical recommendations for, hopefully, making things work better. Nothing is being watched more closely than the President’s foreign policy. Now that many of the top diplomatic, military, and national security advisors have been chosen, the real work begins of deciding the future of America’s place in the world.

FACTOID: The Question: Will Trump foreign policy make the U.S. more safe?

Will the United States remain the dominant force on the global stage, or is that a position shifting to China, Russia, or even Europe? Could we be on the brink of new wars? Are we entering an era of hostility or friendship with Russia?

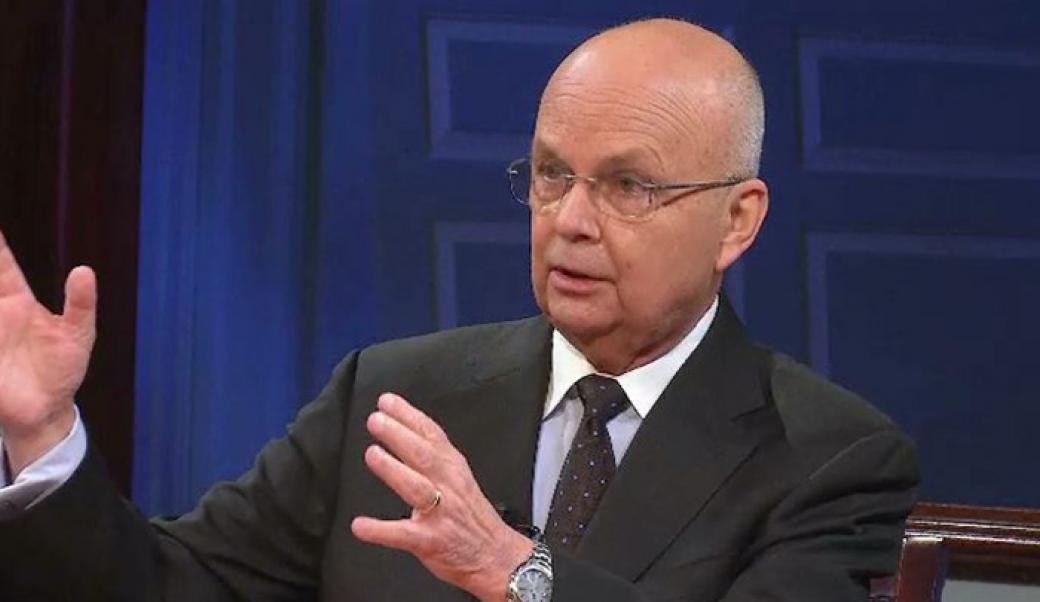

2:20 Blackmon: Our guests today are two eminent foreign policy experts. One is a conservative who tried, at least briefly, to work with the Trump transition team, and whose past history put him on the front lines of the war in Iraq. Eliot Cohen was counselor to Secretary of State Condoleezza Rice in the Bush administration. He’s also the author of a new book, The Big Stick, which argues for a strategy of heavy-duty military force, and the limits of soft power. Our second guest predicts that President Trump may quickly lead us into new military conflicts. Jeremi Suri is a history professor at the University of Texas, and author of eight books on politics and foreign policy, including a biography of Henry Kissinger. His upcoming book is entitled The Impossible Presidency: The Rise and Fall of America’s Highest Office. He recently wrote an article in American Prospect magazine, contending this early period of the Trump presidency brings us to a dangerous new precipice in many parts of the world. Thank you both for being here. [Jeremi Suri: Thank you.] [Eliot Cohen: Good to be with you.] Jeremi, I just mentioned in the intro the article that you wrote in American Prospect recently. These are a few very short lines from it: “Trump’s presidency will be defined by war”; “a dangerous new precipice”; “The United States will be more reactive than strategic; more belligerent than cautious; more isolated than it has been since before World War II.” Why is it as bleak as all of that?

Suri: Well, I think we’re in a very challenging world right now, Doug, and the issues we confront in so many regions—from the Middle East, to the South China Sea, to North Korea, to our relations with Russia—are incredibly delicate. They involve a large number of players, and, most significant, American power cannot determine the outcome. And we have a president and a team that are not very well-informed, and have shown very little inclination to get themselves well-informed. They might have excellent intentions, but the history of American foreign policy is the history of the United States stumbling into conflicts because the United States is not well enough prepared, and because the United States does not understand the legacies of commitments it’s made perhaps in an earlier time in a particular region.

4:36 Blackmon: But I want to make sure that we understand what you’re suggesting. Is it—are you suggesting that—I mean, is—are you really predicting that there’s a sequence of events already in motion that you imagine us moving into expanded warfare, continuation of the war we’ve been involved in for 15 years? Or are you just saying there are big risks in the world?

Suri: So, the historian in me sees many familiar historical patterns that in the past have taken us to wars in places like Korea, Vietnam, Persian Gulf, and elsewhere. Those patterns are in place today. I wrote the article not because I want us to go to war, nor am I predicting.

FACTOID: Suri’s article was in January 3, 2017 edition of The American Prospect

I’m hoping that if we see these patterns we can perhaps shift direction and avoid falling into war, and I’m hoping that the Trump administration—which I want to believe wants to avoid war—will take those historical lessons to heart. And I don’t necessarily have a solution in any of these regions, but I want us to— [Blackmon: Typical historian.] Exactly. But I want us to recognize the danger. I want us to recognize the danger.

5:35 Blackmon: Well, and I want to come back and work through some of that in more detail, and hear what Eliot Cohen thinks about it, as well. But first, tell us about your encounter with the Trump transition, that you’ve written about, has been much discussed about. You were a person who—a prominent conservative foreign policy scholar with experience in the Bush administration. You were part of the Never Trump group, where, essentially a long, long list, the vast majority of identifiable conservative foreign policy, influence and—influential people and thought leaders signed on to a couple of different letters and said—opposed to Trump under all circumstances.

FACTOID: “Never Trump” letter called his vision “unmoored in principle”

You were part of that, but then after the— [Cohen: I was one of the ringleaders. (laughter)] You were one of the ringleaders, yes, and we’ve had several of your co-ringleaders at this table over the past year. But so, then what happened after Mr. Trump was elected?

Cohen: So my, you know, I was surprised, not shocked, when he won. And I thought hard about it and said, well, look, let’s give these folks a chance. And I did say that I thought if—I said you should always have your signed, undated letter of resignation in the top drawer of your desk, because almost any form of government service sooner or later involves coming up to a point where your integrity is going to be on the line. So that would be general advice, but particularly in this case. And then I was approached by a member of the transition team, who I continue not to identify, to ask, ask me for some names, and I gave them some names. And then, for a relatively senior position, I said, “Well, I’ve talked to so-and-so. He doesn’t want to actually sort of apply for it. He’d be willing to have a conversation.” And I just got a blast of hostility back, which—that did shock me, because this was from someone who’s quite serious. And between that and a lot of other collateral information, it just occurred to me that the transition teams, at least, were kind of hostile, belligerent, rather vindictive. And in general, my sense was—and to some extent still is—that, you know, you should stay away from large parts of this administration, because it’s going to be very ugly. Now, I think there, there are variations. You know, if you’re working for a Secretary Mattis in the Pentagon, that’s one thing, but the White House is something quite different. And let me say one other thing, which is, I mean, I share many of Jeremi’s concerns, but my concerns are really built not so much around experience but around temperament. And that was at the heart of those two letters: our concerns about character, and our concerns about judgment. And, for me, those are the most important things.

8:20 Blackmon: What’s the argument that if somehow he ends up with the best people around him everything might actually be okay?

Cohen: Well, so, I mean it will not be normal, (laughter) but it might be abnormal and kind of okay, or it might be abnormal and seriously not okay. We just don’t know. So the optimistic scenario would go something like this: that Trump really is not particularly interested in foreign policy, he doesn’t know a whole lot about it, uh, but he has a reasonably capable secretary of state and secretary of defense and director of national intelligence, and so on, and he is essentially willing to delegate a lot of the work of foreign policy to them. Now, that’s hard in our system, given the power of the president, and that is the optimistic scenario. I’m not entirely sure I believe it, but it’s certainly a, a possibility.

9:12 Blackmon:, I mean, it’s optimism based on the possibility of absence, really. [Cohen: Yes.] Yeah, (laughter) that he just wouldn’t really be—wouldn’t direct our foreign policy, and so the various conflicts—

Cohen: I mean, even under the optimistic scenario, you know, let’s just consider that early-morning tweeting that he’s so famous for.

FACTOID: Trump has sent 32,000 tweets since 2009, has 19 million followers

Now, some people view him as sort of the ninja master of the tactical tweet, and other people think this is just an impulse control problem. The point is, though, that, you know, when you have a president sort of letting loose with all kinds of very short sentiments, which then have to be walked back the next day by his spokesman, we have a very serious problem with our credibility. I mean, we may find ourselves walking into the same, or, indeed, a worse version of the problem that President Obama had, which is the red line that wasn’t a red line. Well, you could have that sort of thing with tweets, and that’s a serious problem, because the credibility of the United States matters a lot.

10:14 Blackmon: Yeah, and tweets can be walked back; cruise missiles can’t. A tweet and the nuclear codes are not very similar to each other, but a tweet and a cruise missile is a little closer.

Cohen: Well, but the tweets are important. You know, it is tremendously important for American foreign policy that people think that when the President of the United States says something, by golly, he means it. And when you throw that away, you’re not only weakening your foreign policy—that’s bad enough—you’re making the world a much more dangerous place.

Suri: But there’s also the question of how you understand American power. And here’s where I think Eliot and I largely agree, but we might have some disagreements. The United States, since 1945—and, really, going back before 1945—has built an architecture for power in the world that’s based upon not just personal relationships between leaders—whether you like Putin or not—but based upon cooperation between various institutions in our own country and institutions in other countries, as well as international institutions. So if you think about NATO: NATO is not just about the heads of state.

FACTOID: NATO was set up in 1949 to block expansion by the Soviet Union

NATO is about the integration of defense capabilities. It’s about the integration of strategic thinking between the United States, Great Britain, Germany, and other societies. And we could say the same about other regions of the world. When you have an administration that doesn’t take that seriously—and the President of the United States doesn’t; in fact, he mocks that—that is exactly what worries me. And that is more than just temperament; that is a paradigmatic, conceptual problem. We have not had a president since 1945, since Franklin Roosevelt, that did not take that security architecture seriously, and that, to me, is a very worrisome issue.

Cohen: I would just say I’m in violent agreement with that.

11:52 Blackmon: Is it possible that President Trump, for whatever reason, intentionally or accidentally, is stumbling into what is, in fact, a fairly important reconsideration of these things, and people like Secretary Mattis, defense secretary, and the secretary of state may have reasonably good answers for that?

Cohen: It is absolutely legitimate, indeed important, to raise those issues. That’s actually the first chapter of that book. But that—raising those in a serious, considered, careful, deliberate way is one thing. You know, getting at this question by firing off random feckless remarks at 3:00 a.m. in 140 characters or less is not a good way of doing it.

FACTOID: Cohen’s new book The Big Stick argues for strong military presence

Suri: And there is also a conceptual issue there, as well: what are we seeking when we reform these alliances? I agree a hundred percent with what Eliot said. We have a lot of legacy institutions that need reform, that need rethinking, but we also have to have a serious discussion before we do that about what we’re reforming them for. [Cohen: Right.]

FACTOID: Suri also believes CIA, NSA, DIA, FBI, among others need reforming

What is our goal? What is our worldview? And what was striking about this entire presidential election cycle—and this applies to both major candidates—is there was not a serious discussion in this troubled world we live in about the kind of world we as Americans want to see going forward. In some moments President Obama has tried to have that conversation. He has also been ineffective. And just as, as Eliot said so well, we’re in a new space now where the challenges are greater than perhaps they’ve ever been. And we can’t reform institutions we’re unhappy with if we don’t know what we’re reforming them for.

Cohen: Right, and I would just add one other thing: as a good conservative, I don’t think you go around smashing the 65-year-old crockery that you have in the cabinet just because you think it’s been there for 65 years, so therefore it’d be a good idea to smash it.

13:43 Blackmon: Yeah. And so let’s talk about some specific places in the world. Let’s start with Russia. President Trump is the president now. We have a sense of who at least the top leaders are going to be in terms of foreign policy. But so what might be the best approach in Russia that a Trump administration could take that you could imagine, based on your observations of the president, that you could imagine would be a foreign policy that he would find acceptable? What would the behavior of the United States be with regard to Russia?

Cohen: Well, the first and most important thing he has to do is stop talking about Vladimir Putin as if he’s a credible figure, and stop talking about Russia as if it is actually really a sort of viable partner in large parts of the world.

FACTOID: U.S. Spends more on defense than next seven countries combined

I mean, I think the first thing you have to do is be realistic about what Russia is, what Putin’s Russia is, and what their objectives are. There is a very serious challenge, I think, coming our way in Eastern Europe, particularly in the Baltic States, which are part of NATO, which we are pledged to commit to defend under Article 5 of the North Atlantic Treaty.

FACTOID: Baltic states of Estonia, Latvia, and Lithuania were seized by Soviets

And I think the most important thing he could do would be to make it clear that he personally takes those Article 5 commitments very seriously, and—in other words, we need to deter the Russians from doing something that I think otherwise they may be tempted to do. [Blackmon: Which would be?]Which would be to conduct a sort of aggression, pressure against the Baltic states in particular.

FACTOID: Russia perceives recent U.S. troop increase in Poland as threat

Not an outright invasion, but something kind of like the things that have happened in the Eastern Ukraine, with the avowed purpose of triggering a crisis where they invoke external support under Article 5, and people just don’t show up, because if that happens, NATO is finished.

15:33 Blackmon: Jeremi, you’ve written or said we could well have a hot war in Europe. I mean, you’re imagining this scenario. How would that happen?

Suri: So, yes, so I—this just builds on what Eliot said. I think it’s quite clear—I think the evidence is overwhelming that the Russian government has pursued a policy of trying to undermine liberal democratic order wherever it can, that Putin is not simply fighting a strategic game in the near abroad, but is seeking to weaken liberal democracies around the world. He sees them as a threat to his regime. He is acting in our country as a terrorist, to try to tape the President of the United States and then use that information against the President, to steal information, right? This is what terrorists do, right? This is terrorist-like behavior. And I think the Trump administration—and maybe it will do this—has to first of all call it what it is, and then the Trump administration has to respond to it. Now, that does not mean we have to go to war with Russia, but it means that the Russian government has to see that there will be costs to this behavior, and that we will not allow this to continue when there’s an election going on in France and in Germany in the coming year. How do we go to war? We go to war if we don’t respond and this continues, and we see further disintegration of democracies in Europe. Why does that lead to war? Because the hinge of peace and stability in Europe since 1945 has been democratic development. That is a Democratic and Republican position. It happens to be historically true. If we allow democracy to be undermined, if we allow Vladimir Putin’s terrorist, antidemocratic activities to succeed, we will see the disintegration of the postwar order, which is likely to bring us to war in the Baltics or somewhere else.

17:11 Blackmon: How then does the United States honor its NATO commitments and its commitments to those countries without entering into a sequence of events that leads to a disastrous kind of war?

Cohen: It’s, you know—part of the problem that we’ve got now is—and this is a legacy, in a way, of the, the past 60 or 70 years—that we think of a lot of our commitments as a kind of strategic pixie dust that you can sprinkle over problems and they go away; so you say “Article 5” and the problem goes away. No, Article 5 is a serious commitment.

FACTOID: Article 5 of NATO Treaty sets up common defense of all members

If you don’t believe in it, withdraw from the North Atlantic Treaty, but if you do believe in it, you better have forces on the ground so that the Russians know that if they roll into Estonia, they’re going to run into American tanks.

Suri: And what I fear is that President Trump might believe that if that scenario happens, that one big act on his part might then discourage Putin. But, in fact, once you’re down that road—this is the historical point—that once you go down a road toward war, it’s very hard to turn off. And so he will feel—I think President Trump will feel, for the right reasons, that he has to respond, maybe not under precise NATO commitments, but he’ll feel he has to respond if Vladimir Putin invades one of the Baltic countries, but his response—he might think can forestall further conflict. But it will actually further escalate the situation, particularly if he’s unprepared for what comes next. Sorry.

Cohen: And this is why, you know, it’s very important to put forces there now, because your best chance of preventing this from happening is if you have substantial armed forces there so the Russians know what they will encounter. It’s military weakness, which is going to make it more appealing to Putin.

FACTOID: Cohen believes U.S. should spend four percent of economy on defense

And Putin is not a crazy guy, and I think he is, in certain cases, risk-averse, so you want to make sure that he understands that it’s a very high level of risk if he tries something like that.

1900 Blackmon: And so would both of you agree with the idea that a very wise first step by President Trump, very quickly in the—after the—very quickly in this first year, that a wise step would be movement of troops, obvious, preparation in the Europe hot zones?

Cohen: Yeah, what I would say is, you know, first I would draw a distinction between NATO and everywhere else. I mean, it’s the NATO countries where we really do have these kinds of commitments. And although I’m sure it would pain him and many others to admit that there’s a certain element of continuity with the Obama administration, the fact is the Obama administration—kind of grudgingly and rather late, in my view—has begun more deployments of forces to Poland and to the Baltic States.

FACTOID: More U.S. troops are expected to join recent deployment in April

And so what I think you need to do is you build on that. Part of the good news, I think, in a Trump administration is we’ll get rid of sequester, we’ll be able to expand the Army again somewhat. You know, we got to the point where there basically—we had no tanks in Europe, which is astounding.

FACTOID: Sequestration: Part of 2011 Budget Control Act cutting defense budget

Well, that was dumb, and so you want to, again, have forces permanently stationed in Europe, and, I would say, permanently stationed in the Baltic states and Poland—not rotating but permanently stationed. During the Cold War we had over 10,000 soldiers in Berlin, a city completely surrounded by Warsaw Pact territory, and the outcome, as we all know, was very peaceful, because the Russians understood if you try to take Berlin you’re going to be in war with the United States, and it, quite sensibly, did not want that.

Suri: And there’s another side to containment that I think is even more important. I hope that Secretary of State Rex Tillerson, that President Trump will spend a lot of time personally reassuring our allies. They need to believe—this comes back to Eliot’s point about credibility—not just that we have the capability, but that we are committed to doing this. Since the end of World War II through to the present, our European allies, our Western European allies, have been pretty firm—Charles de Gaulle questioned this at certain moments, but with some—with few exceptions have been pretty firm in their belief that the United States would come to their support if the Russians came through the Fulda Gap. We need to restore that faith, because that faith has been shaken in a way I never expected it would in my lifetime.

FACTOID: During Cold War, ‘Fulda Gap’ was hypothetical Soviet invasion route

21:16 Blackmon: And it’s almost impossible to imagine that Secretary of Defense Mattis, of all the people that we’ve referred to here—there is no way that Secretary of Defense Mattis would remain a part of a government that was not going to honor those commitments. Is that a fair thing to say?

Cohen: Well, during the transition I testified to the Senate Armed Services Committee on exactly that point, and I’ve made the very strong case that I think he would be a voice of sanity and moderation and consistency and strength, which is exactly what we need.

FACTOID: Cohen testified to Congress on civilian control of the military

And I’m—you know, again, if you want me to be hopeful, I would say the fact that the President was willing to pick Mattis, that’s a good thing, and I think Mattis will be a very sound voice within this administration.

Suri: I think it’s a very bad thing that—I like Secretary Mattis, but I think it’s a very bad thing that we’re relying upon the Military to discipline the political leadership, and our allies in Europe who recognize and understand our system will recognize that as well. It is not as credible when it’s only coming from the secretary of defense. It has to come from the president of the United States.

Cohen: Yes, I agree. I agree with that.

Blackmon: You, Jeremi, in particular, have written about, talked about—but you’ve both talked about the importance of diplomacy in addition to force. The—in terms of China, which is more of a diplomacy situation, I think, than the kind of military scenario that is already—has to be part of the discussion as far as Europe. President Trump would probably find appealing the idea that if China continues to interfere with—in the South China Sea, and to try to effect territorial boundaries, and obstruct commerce, that if they get too close, we’ll just sink one of their ships. I mean, I think that idea—that’s a hard force approach, and I think President Trump would probably find that appealing.

Cohen: Who knows? I mean— [Suri: Dangerously so, yes. Dangerously so.] Our challenge with China is this is going to be a complicated, very mixed kind of relationship. We do a huge amount of business with them. We want to continue to do that.

FACTOID: China is largest U.S. Trade partner, totaling $659 billion in 2015

At the same time, we don’t want them to push us out of Asia. We do want to reassure the countries on their periphery, and so we are kind of managing what is, in fact, a kind of coalition to balance China. And I’d come back again to that idea of consistency, sort of a uniform message.

Suri: I think the best approach to East Asia and the South China Sea is the approach the Obama administration announced but did not follow through on, which is to actually help to strengthen our allies in the region. Our best asset is that most of the countries we care about in the region other than China are even more frightened of China than we are, and are desirous of working with us, even if they have reasons, historical reasons, not to work with us. Think of Vietnam as an example.

24:02 Blackmon: So, you say that the two of you are not going to sit down with President Trump anytime soon to reprise this conversation, so one piece of advice for President Trump in the first year of his administration.

Suri: I think it’s absolutely crucial that he understand the nature of our alliance relationships with our key partners in Europe and Asia, in particular, and that he cultivate and build on those relationships, and avoid erratic statements that could undermine those overnight.

Cohen: Stop the goddamn tweeting. (laughter)

Blackmon: Eliot Cohen, Jeremi Suri, thanks for being here. [Suri: Thank you.] If you’d like to join our conversations about national security, politics, or any of the central decisions facing our new president, go to the Miller Center Facebook page; visit MillerCenter.org; follow us on Twitter—my handle is @DouglasBlackmon; you can reach our guests at @EliotACohen and @JeremiSuri; or keep watching us on your local PBS affiliate. Remember, in the coming weeks American Forum will continue this kind of discussion and its focus on the first year of the Trump presidency, with episodes looking at the state of the American dream, our broken government, immigration, and other critical issues. Upcoming guests will include famed Civil War historian Gary Gallagher, and Washington Post columnist E.J. Dionne. For more about our First Year Project, go to the website, FirstYear2017.org. I’m Doug Blackmon. See you next week. (applause)